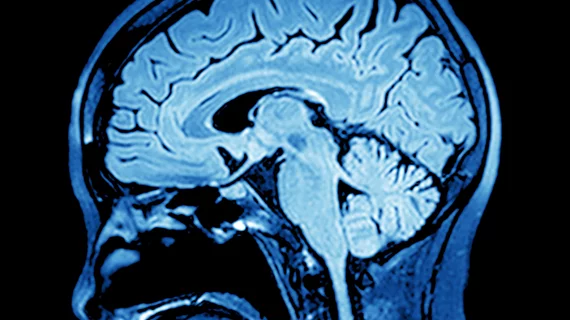

Stanford researchers have developed an AI tool that can help diagnose damaging brain aneurysms that can have potentially fatal effects.

The development of the tool was detailed in a paper published June 7 in JAMA Network Open that examined a diagnostic study of intracranial aneurysms.

Researchers used a test set of 115 examinations that were reviewed for the presence of an aneurysm with model augmentation and once without in a randomized order by eight clinicians. Compared to the reviews without augmentation, the examinations with augmentation were more sensitive and accurate, helping clinicians make a difficult diagnosis.

The tool developed in the study was built around an algorithm called HeadXNet, and helped clinicians find about six more aneurysms in 100 scans that contain them. To train the algorithm, researchers used 611 computerized tomography angiogram head scans that had clinically significant aneurysms.

With high health stakes associated with aneurysms, including stroke or death, having another tool to help doctors save lives in this area is “highly desirable,” the researchers stated in their study. For example, aneurysm rupture is fatal in 40% of patients, while two-thirds of those who survive end up with an irreversible neurological disability.

“Search for an aneurysm is one of the most labor-intensive and critical tasks radiologists undertake,” Kristen Yeom, associate professor of radiology and co-senior author of the paper, said in a statement. “Given inherent challenges of complex neurovascular anatomy and potential fatal outcome of a missed aneurysm, it prompted me to apply advances in computer science and vision to neuroimaging.”

Without augmentation, clinicians achieved a microaveraged sensitivity of 0.831, specificity of 0.96 and an accuracy of 0.893, compared to microaveraged sensitivity of 0.89, specificity of 0.975 and accuracy of 0.932 with augmentation.

While the algorithm isn’t intended to replace the role of a doctor when making these diagnoses, the AI tool can help comb brain scans faster and diagnose trickier images.

“There’s been a lot of concern about how machine learning will actually work within the medical field,” Allison Park, Stanford graduate student in statistics and co-lead author of the paper, said in a statement. “This research is an example of how humans stay involved in the diagnostic process, aided by an artificial intelligence tool.”

Still, the Stanford researchers argued that more studies should be done to evaluate the generalizability of their AI tool before it’s used in real-time settings.