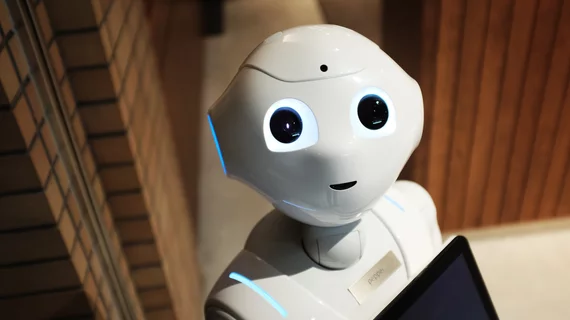

Many parents would let their children be read to by robots, zoomorphic as well as humanoid, as long as the device didn’t project a little too much lifelikeness.

That’s called the uncanny valley effect—the common human tendency to recoil from robots that resemble sentient beings and seem to possess a will of their own.

It appears as a steep dip on a likeability graph, hence the name, and it’s on full display in a study conducted at Indiana University and posted in Frontiers in Robotics and AI.

Senior-authored by computer scientist Karl MacDorman, PhD, the study shows some participating parents expressing ambivalence in pointed terms.

“You remember those Furbies? Those things would just start talking out of nowhere, and it scared people,” says one. “If the robot could just wake up and start telling a story in the middle of the night, if it started talking on its own out of nowhere, I think I would be scared of it.”

Another: “If the robot was like, ‘What’s your dad’s social security number?’ I might freak out.”

However, misgivings were often offset by positive reactions.

“If I had an especially busy night, and my husband wasn’t home, and it was time to do story time,” offers one mom, “that would maybe give me 10 minutes to pack their lunches while they listen to their story from the robot.”

For the project, the team recruited 18 parents and used two robots.

The zoomorphic character, Luka, is a hard plastic owl that reads picture books while parent or child turns the pages.

The softer, human-shaped Trobo looks like a Muppet with drawn rather than movable facial features. It reads ebooks via Bluetooth.

After completing online surveys asking about demographics and family dynamics, the parents and their children met with the researchers at home or in the lab for robot reading sessions with Luka and Trobo.

In semi-structured interviews following the sessions, the parents were asked to refrain from reviewing the two specific robots and, instead, to imagine a “futuristic robotic concept” when giving their input.

Upon systematic analysis of interview transcripts, the researchers arrived at five primary findings:

1. Despite concerns, parents were generally willing to accept children’s storytelling robots.

2. Some parents viewed the robot as their replacement, a “parent double.” By contrast, they viewed screen-based technologies as a way to keep their children occupied when they are busy with other things.

3. Parents valued a robot’s ability to adapt and express emotion but also felt ambivalent about it, which could hinder their adoption.

4. The context of use, perceived agency and perceived intelligence of the robot were potential predictors of parental acceptance.

5. Parents’ speculation revealed an uncanny valley of AI: a nonlinear relation between the perceived human likeness of the artificial agent’s mind and affinity for the agent.

The study’s lead author is Chaolan Lin, a PhD candidate in cognitive science at UC-San Diego.

Lin et al. comment:

Our findings showed that parents had ambivalent though generally positive attitudes toward storytelling robots and were willing to accept them in the home. Parents valued storytelling for their child’s literacy education, habit cultivation and family bonding. These goals provide a framework for assessing the usefulness of storytelling robots.

We also introduced the concept of an uncanny valley of AI to explain some of the parents’ ambivalent views. Parents found it difficult to establish a mental model of how a robot with a social capability operates, which creates cognitive dissonance and a feeling of uncanniness. This feeling might be mitigated by making its AI more transparent and understandable.”

The study is available in full for free.